Besides carrying out several other types of surgeries, for most of my career, I have had the privilege of looking after patients who are the victims of trauma - i.e. the work of a trauma surgeon. I therefore have insights into the care of the injured that may be of interest to my readers. I have not been in war zones, but my father was a Naval surgeon and I have imbibed much from living with and learning from him. In addition, I have researched, written about and published surgical and medical history as it pertains to war.

I will therefore take my reader deep into the heart of a modern trauma surgery unit; then describe the horrors of surgery before the advent of anesthesia and antisepsis.

And then, with a heavy heart, tell you heartbreaking stories of the care of war wounds in a modern area of conflict, which has descended to conditions not very different from about 170 years ago. As a surgeon, my readers will understand that this has weighed heavily on me - as it has no doubt, on the collective conscience of humanity.

Even before a victim of trauma is received in a modern trauma centre, ambulance and fire fighting services have extricated the victim and skilled paramedics then immobilize the victim and carry out life-saving measures such as the application of tourniquets to stop exsanguinating bleeding from the extremities, start infusing intravenous fluids etc. In addition, they are able to administer generous doses of powerful pain relievers (most are derivatives of morphine) at the time of extrication and during the frenzied trip to the trauma centre. The trauma centre is notified about the patient coming in - and the trauma team swings into action.

Once in the the trauma centre, the hospital paging system sends out several, blaring overhead messages about the arrival of the patient. Surgeons, anesthesiologists, residents and nurses then take over the care of the victim of trauma. Once again, generous doses of pain killers are administered, since shattered bones, amputated limbs, stab and gunshot injuries and blunt injuries of the chest and abdomen can be excruciatingly painful. This time, expert anesthesiologists can titrate the pain killers according to need and also take over the care of the breathing of the patient.

The surgeon then has many different decisions to make, several within split seconds. Sometimes, an immediate procedure is needed to save life - such as letting fluid out of the chamber that surrounds the heart or putting a tube into the chest to let out large quantities of blood, which would otherwise crush the lung and suffocate the patient; and sometimes, if the airway is blocked and swollen, the surgeon will do what is called a “tracheostomy” (a surgical opening into the windpipe). All this is done with what is called “aseptic technique” - in other words, in a clean and sterile field. And once again, generous doses of local and general anesthetic are always available.

Multiple other specialties can now be activated if necessary, including neurosurgery (for brain and spinal injuries) and orthopaedic surgery (for bone and joint injuries). The general and trauma surgeon then decides whether immediate, life saving surgery is required, for example to remove a ruptured spleen or repair a ruptured liver.

Following the surgery, the severely injured patient is received into the Intensive Care Unit - where again, pain relief is always available. After what may be several days or several weeks, the patient is discharged from the ICU, to begin what is often a long road to recovery.

My readers will note that my account of the workings of a modern trauma unit makes several assumptions - that prompt and expert rescue of the victim of trauma is available; that adequate and effective pain relief is always administered; that antibiotics are always at hand and appropriately used; that anesthesia is essential for both minor and major surgery; that antisepsis (clean and sterile operating conditions) is essential for a good outcome; and that intensive care after major trauma surgery is a feature of modern trauma care.

In contrast, before the advent of anesthesia (1846), all operations were performed in almost completely awake patients, without anesthesia, as in the illustration below:

My readers will notice not only the agony in the face and demeanour of the patient, but also that the operation is being done by surgeons in street clothes. This is because it was not until about 1882 that antisepsis (clean surgery) became accepted in the surgical community. Before antisepsis, almost all hospital wounds from surgery became infected and most infected patients died.

Very basic anesthesia with chloroform was available in the Crimean War (1854-56 ) but adequate pain relief during and after the surgery was all but completely absent. This was before the advent of antisepsis - so infection, foul odours, maggots (the larva of the fly) in wounds and patients crying out for help (with no help anywhere near) were common. Amputations were the commonest operation - and patients often screamed in pain before, during and after the surgery.

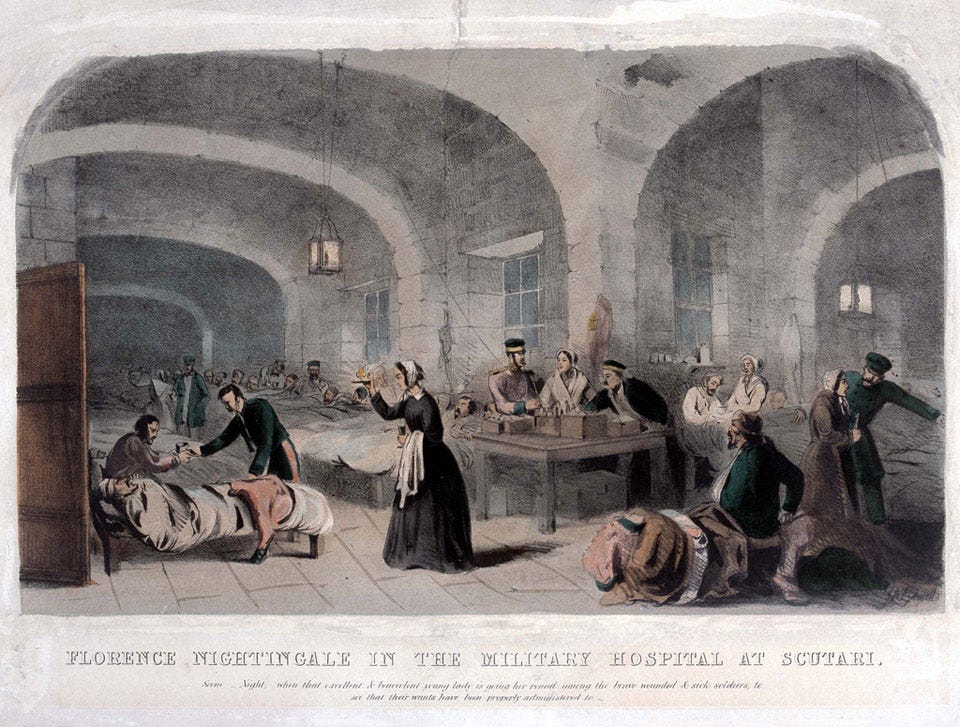

Into this cauldron of suffering, strode a very determined English nurse, who, within a few months, had cleaned out the floors of the British hospital in Crimea, brought in clean linen, thrown open the windows to let in fresh air and light, arranged the patients in orderly rows, introduced hand washing and most importantly, worked very long hours to comfort, cheer and palliate the injured soldier - and it was said that soldiers would stay awake and wait for the flicker of light that would turn into the glow of a lamp, lighting the face of Florence Nightingale, the “lady with the lamp.” And thus was modern nursing born.

The discovery of anesthesia has been called the greatest discovery ever made in the long and turbulent history of man - I believe there is much truth in this assertion, since the horrors of surgery without anesthesia are unimaginable. And the other great discovery of antisepsis (also in the 19th century) transformed surgery and made it immeasurably safer. Much later, the discovery of Penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming was to save countless lives in the second world war (before the introduction of randomized control trials in medicine).

As a surgeon, I do not need to take sides in a war or conflict. So those of my readers who are looking for something in this essay as betraying a taking of sides, will be disappointed. I make no assumptions on the cause of the conflict or its conduct. I simply bring my readers’ attention to the heartbreaking plight of the injured, particularly gravely injured and orphaned children - and then I shall let you make your own assumptions and conclusions.. In this way, without taking the side of either party, it is possible to be on the side of humanity, of the innocent, injured civilian casualties of war.

Of the 18,000 people killed in Gaza in the last two and a half months, more than 8000 are children. But it could be argued, that the departed dead are better off than the living - since many thousands more children are seriously injured or orphaned. Many have lost limbs and many have needed amputations.

A child cries in pain, lying on a stretcher at Nasser Hospital, Southern Gaza (Picture: Abed Zagout/Anadolu via Getty Images)

Because of the lack of basic medical supplies in the besieged enclave of Gaza, doctors in the Gaza hospitals have had to do amputations and Caesarean sections without anesthesia. Operations on children too have had to be done without anesthesia. Hospitals that are supposed to have a 400 bed capacity are inundated with the injured and have more than 3,500 patients, many on the floor, most without basic surgical care or pain relief. And the numbers are increasing all the time.

More than 200 health care workers have now been killed in Gaza, among them more than 50 doctors.

Yesterday, the CNN chief international reporter Clarissa Ward was allowed into Gaza, to report from the only fully functioning hospital in Gaza, close to the border with Egypt. Her report is shattering - and I could not help weeping with her, as she comforts a child:

A very brave American nurse returned from the hell that is Gaza a few weeks ago. She describes what it was like to work in the Medicine Sans Frontier hospital in Gaza:

Gaza now has severe shortages of food, water, doctors and medical supplies. So in addition to operations without anesthesia and with a constant challenge to keep things clean in the operative field, the besieged city of Gaza is thirsty, hungry and on the brink of being swamped with epidemics.

We cannot allow this to continue. Both sides have suffered grievously and there is no end to the night of suffering in Gaza in sight. There are those on both sides who want peace - perhaps this is a good place to start. I don’t know. But humanity cries out for deliverance. For an urgent, immediate ceasefire - surely that is an indispensable first step. Deliver us O God! Deliver the children!

So heart felt. I pray for the end of this killing. It’s unimaginable and saddens me to my core.

I join with you dr Christian in praying for the end to the agony of war -

Maranatha.